Our Young Percussionists Are Not Being Trained to Be Musicians

In South Florida, where I was raised, most kids don’t experience percussion until they’re in the 6th grade (11 years old). Typically, this experience is not in a space comprised of other percussionists, but rather in a wind ensemble or orchestra setting. A bright-eyed percussionist, likely with his or her beginner stick bag, rented beginner bell kit, snare drum, and pad are prepared to do what every instrumentalist is there to do — learn to make music.

Or so they think.

The typical band director is equipped with many of the tools and training needed to make their wind players sound good. They instruct them on proper posture and spends time working on breathing in preparation for playing together as an ensemble. Then they all begin working on their sound. Well, except for the percussionists. Percussionists may learn a scale pattern created for wind players, and maybe a snare rhythm to pair with it. Band directors often focus their energy on helping wind players listen to the sound they’re creating and blending that sound with their section, then honing in further on good posture and breath control. If percussionists are lucky enough to be involved in these parts of rehearsal, the sounds they are creating are often ignored.

Take this common situation:

The beginning band is tasked with playing a Bb scale in half notes. The percussionists get on their nearest xylophone, grab a pair of mallets from their beginner set, and begin playing half note rolls on each note up the scale. The rolls don’t sound good. The mallets don’t match. They may or may not be striking all over the bar with no regard to proper playing areas. Maybe they receive some feedback on dynamics (meaning they are playing too loud), but more often than not, they’re told to stop playing while work is being done creating solid sounds with the wind players.

To an extent, I understand why this situation occurs. Common percussion instruments produce immediate feedback. If you ask a student to play a Bb, the desired pitch sounds immediately upon striking it. With wind players, a lot more goes into basic sound production so a lot more time is spent focused on them and that trend often continues throughout their middle school band experience. The snare may not be tuned, the head may be dead, the sticks may not match each other, and the bells mallets may switch with each run. However, more immediate concerns of wind issues cause the majority of band directors to marginalize percussionists and ignore key parts of their training, putting them at a serious disadvantage.

The problem doesn’t stop there. Percussionists entering high school will finally be exposed to larger keyboard instruments, and getting specialized instruction for the first time. This could be a wonderful opportunity to build a really solid musical foundation, but unfortunately the first half of the year is marching band. This stinks because I love marching band! But the harsh reality is that the standard keyboard education for marching band can be very damaging and often leads to students becoming technically proficient, but musically deficient.

Here are a few of the causes:

- Because of the nature of the marching band activity, priority is given to the visual before the aural.

- Hours are spent “chopping out” — focusing on building muscle strength by using aggressive methods to gain speed and height while micromanaging the smallest details of each persons fingers with little regard to musical nuances.

- Using primarily pattern based unison exercises that work singular facets of technique with minimal listening responsibility.

- Dynamic nuances are replaced with contrasting extremes for effect.

- Hard and fast rules are created to help players appear visually aligned (ex. play only in the center of the bar).

- Instructors that are there solely to compete without any thought given to how their approach will affect the overall development of percussionists as musicians.

- Aggressive, and often times unhealthy techniques are used despite the progressive use of amplification in the marching idiom.

- The first time a high school percussionist picks up an instrument outside of marching band is months later.

- The demand to memorize only an average of 15 minutes of music per year drastically diminishes their reading skills.

- The pressure to learn that music quickly leads to rote memorization and heavily impedes on their ability to learn high quantities of music proficiently.

The bottom line is this. While students are in one of the most critical points in their musical development, we tend to marginalize the player’s ears, strip away their musical choices, handicap them from being able to curate their own sound, and harden their touch.

As a result, most young adult players experience these challenges:

- They have very little touch or control on the instrument.

- They determine the quality of pieces and parts by the technical demands as opposed to the musical demands.

- They’re unable to curate their own sound.

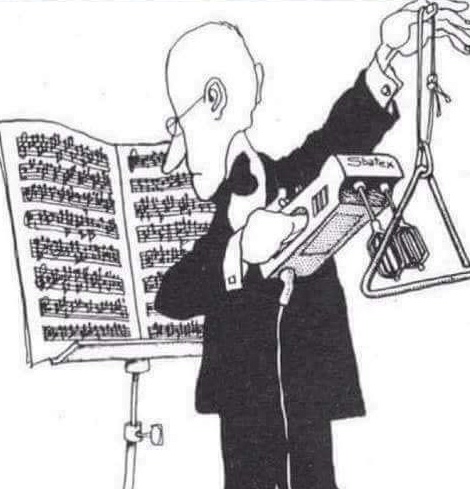

- They’re unaware of the multitude of choices they have and how these choices can add value to their ensemble (ex. what type of cymbal to use for a piece, or what beater to use on a triangle).

- They’re unappreciative or unaware of different approaches to the instruments.

- Often, expressing themselves visually becomes mutually exclusive to expressing themselves musically. This detracts from the music as opposed to adorning it.

For many students, this changes when they enter into college. Their worldview is widened. Ear training becomes part of their course curriculum, different types of ensembles are introduced, new peers from varying backgrounds are met, and the caliber/perspective of educators they encounter is significantly raised. The “introductory” levels, however, need to be better. So what can we do?

Here are a few suggestions:

- There is no substitute for a quality private teacher. Encourage ALL of your students to seek one out from day one, and keep the encouragement going in perpetuity. If student’s cannot afford it, encourage them to practice with more experienced students and make yourself available when you can.

- Bring in specialists as much as possible.

- At the start of their development, keep percussionists inclusive in band activities. These include breathing techniques, posture, blending, and balance within the ensemble. These are essential to creating a great sound on all instruments.

- Make sure that percussionists have a strong awareness about the music or exercises being played and not just their individual parts. They should know what is going on throughout the ensemble.

- Encourage your students to buy or rent quality instruments and implements from quality companies. Stock them if need be and provide payment arrangements or rental plans like you do for other instruments so that students can access the tools they need for creating quality sound.

- Invest in the whole percussion section. Have a few high quality mallets for timpani, bass drum, gong, chimes, and mallet instruments. Provide matched sticks for snare drum and toms so that your young musicians can hear quality sounds from the start. Have a few different triangles and beaters, and have an array of cymbal sleeves and felts on hand.

- Encourage young percussionists to make choices from the beginning. How does that cymbal sound? Why would you choose it as opposed to the other available options? How does that mallet choice sound? What wind instrument articulation do you think it most resembles? What sound are you trying to get out of that drum? Do you think there is a better approach or implement to achieve it? Continue this throughout all levels of development.

- When they enter high school, continue helping them curate their sound by always relating what you are asking them to do visually, with how it sounds to them.

- Make the effort to play exercises that not only work the fundamental hand techniques, but also work the ears. Exercises with melodies and harmonic development. “Etudes” that do this can work well in theory, but a majority of these pieces rarely get played. In addition, the idea of separating the physical technique from ear/musicality training seems to be an idea unique to mallet percussion. This is largely due to the fact that much of mallet percussion pedagogy in the marching arts is reflective of developmental approach more beneficial to drumlines.

- If personnel allows for it, create exercises unique to your front ensemble and their musical needs/development as opposed to ones that fit with the battery.

- Stop using inches to measure dynamics on melodic instruments.

- INVEST IN AND CONTINUE TO UPGRADE YOUR OWN SKILLS AND YOUR OWN EAR! If you don’t know the difference between triangle approaches, how do you expect your students to know? If you don’t care about which cymbal is used on a part, how do you expect your students to care? Continue your education past the classroom through seminars and clinics put on by wonderful organizations such as PASIC or your state chapters of Music Educator Associations.

What was your experience?

If you were fortunate enough to have solid musical training in grade school, what were some of the techniques that your educators used to help you become a musician as opposed to a technician during your primary years?

Want to hear more? Click HERE and level up!

Drew Tucker is a musician, social entrepreneur, and cultural iconoclast who lives to help people take massive action towards their artistic goals. He also likes coffee.